Living Near an Asbestos Factory or Mine

Mention mesothelioma and most people picture the victims as those who handled asbestos on a daily basis. Construction workers. Insulators. Tile installers. Welders. Pipe fitters. Steel workers.

Consider a case that was recently brought to light in Japan. A news story in a Tokyo newspaper recently reported that four individuals that lived within 500 meters of each other in a densely populated area of that city – known as the Ota Ward – died of mesothelioma between 2007 and 2017.

Their only exposure to asbestos? They lived close to an asbestos factory that operated near their homes until about 1980.

A Tokyo-based grassroots organization known as The Asbestos Center reports that this is the first time that multiple cases of mesothelioma have been found near a former factory in the capital city.

They fear that more such pockets of diagnoses will pop up in the near future as mesothelioma can take decades to appear. It’s a natural assumption as cases of mesothelioma continue to grow in Japan, which finally banned all uses of asbestos in 2012.

Prior to that, asbestos use was abundant.

“According to doctors and others who saw or knew the four patients, they lived around the factory for seven to 76 years,” reports the story in The Mainichi, a daily newspaper in Tokyo. “Three male patients had lived within a 200-meter radius of the factory and died when they were between 73 and 82. The remaining female patient died when she was 59. She had frequented an area near the factory, which was about 500 meters away from her home,” the story explains.

None of them had work experience connected with asbestos and they had lived near the factory for long periods of time,” reiterated Hirokazu Tojima, a specialist on asbestos-induced illnesses at Tokyo Rosai Hospital.

In the U.S., this story isn’t a surprise.

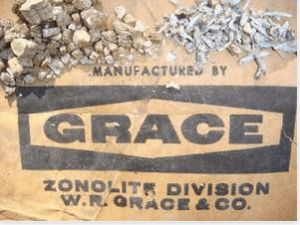

Consider the town of Libby, Montana, where hundreds of residents who didn’t work in the nearby asbestos-tainted vermiculite mine have been diagnosed with mesothelioma or other asbestos-related diseases.

Asbestos dust regularly permeated the air in Libby and asbestos tailings were even used in gardens and – alarmingly – on playgrounds.

As a result of this somewhat indirect exposure, many have died.

The lesson learned should be that asbestos is deadly no matter how small the exposure and that individuals need to remain diligent about avoiding any asbestos-containing materials, especially since it has yet to be banned in the United States and can still be found in homes, offices, schools, factories, and numerous other locations.

The “problem formulation”, which was released for public comment, includes a significant new use rule (SNUR) proposal enabling the agency to prevent new uses of asbestos. The EPA contends that this is the first ever such action on asbestos proposed in the United States.

The “problem formulation”, which was released for public comment, includes a significant new use rule (SNUR) proposal enabling the agency to prevent new uses of asbestos. The EPA contends that this is the first ever such action on asbestos proposed in the United States. It has been reported that the minerals supplier, based in France, did not admit – as part of the settlement – that their talc was dangerous.

It has been reported that the minerals supplier, based in France, did not admit – as part of the settlement – that their talc was dangerous. It’s not as if Hanna hasn’t been caught in the past. He has, but he’s gotten away with minimal fines and suspended prison sentences.

It’s not as if Hanna hasn’t been caught in the past. He has, but he’s gotten away with minimal fines and suspended prison sentences. It’s just the latest in a string of incidents reported in the last two years involving asbestos contamination in city-owned buildings in Texas’ capital city.

It’s just the latest in a string of incidents reported in the last two years involving asbestos contamination in city-owned buildings in Texas’ capital city. Recently, a union representing USDA employees working in Washington D.C. released a statement expressing concern that officials are exposing workers to both toxic asbestos and lead paint. Specifically, the union accused management of “failing to provide sufficient notice about asbestos and lead abatement or to maintain secure, sealed physical barriers between ongoing work and staff at nearby desks.”

Recently, a union representing USDA employees working in Washington D.C. released a statement expressing concern that officials are exposing workers to both toxic asbestos and lead paint. Specifically, the union accused management of “failing to provide sufficient notice about asbestos and lead abatement or to maintain secure, sealed physical barriers between ongoing work and staff at nearby desks.” So, say some, it’s not a far stretch to imagine that daily exposure to asbestos may have caused a long-time employee at this old municipal building to develop lung cancer.

So, say some, it’s not a far stretch to imagine that daily exposure to asbestos may have caused a long-time employee at this old municipal building to develop lung cancer. The workers told a KXAN-TV reporter that they were not provided with the proper equipment to complete the job and are now fearful of the health ramifications of their exposure to the deadly toxin.

The workers told a KXAN-TV reporter that they were not provided with the proper equipment to complete the job and are now fearful of the health ramifications of their exposure to the deadly toxin.